Now Available In Paperback

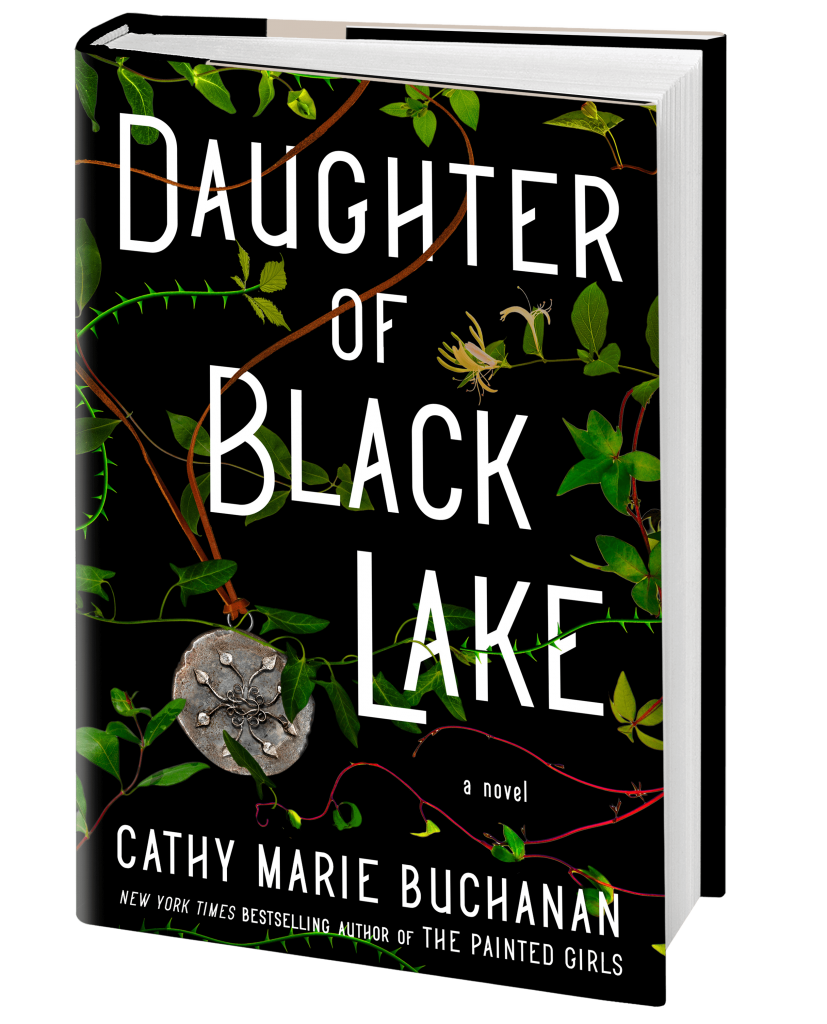

In a world of pagan traditions and deeply rooted love, a girl in jeopardy must save her family and community. A transporting historical novel by the New York Times bestselling author of The Painted Girls.

• Entertainment Weekly's "Best Books to Read This Fall"

• Parade's "Fall's Best New Historical Fiction"

• Toronto Star "Armchair Adventure" selection

It’s the season of Fallow, in the first century A.D. In a northern misty bog surrounded by woodlands and wheat fields, a settlement lies far beyond the reach of the Romans invading hundreds of miles to the southeast. Here, life is simple–or so it seems to the tightly knit community. Sow. Reap. Honor Mother Earth, who will provide at harvest time. A girl named Devout comes of age, sweetly flirting with the young man she’s tilled alongside all her life, and envisions a future of love and abundance. Seventeen years later, though, the settlement is a changed place. Famine has brought struggle, and outsiders, with their foreign ways and military might, have arrived at the doorstep. For Devout’s young daughter, life is more troubled than her mother ever anticipated. But this girl has an extraordinary gift. As worlds collide and peril threatens, it will be up to her to save them all.

Set in a time long forgotten, Daughter of Black Lake brings the ancient world to life and introduces us to an unforgettable family facing an unimaginable trial.

PRAISE

NEWS

INSPIRATION

In 2002, I opened the newspaper to see a photograph of an unnervingly well-preserved 2000-year-old human body.

I could not lift my gaze from the gentle face—the finely creased skin, the matted hair, the beard stubble that appeared as freshly grown as that of any man. The rope noose that brought death was still looped around the neck. The accompanying article explained that the chemical nature of the peat bog, from which the body was unearthed, had enabled the flesh and skin to survive across millennia, providing clues to the world in which the man lived and died.

I would learn that Tollund Man, as the body was named, was not unique. Dozens of similarly unspoiled bodies had been recovered from the boglands of Northern Europe. Each was submerged in a watery grave thousands of years ago, but as time passes, rushes dying at a pool’s fringes begin to fill the water and the thickening stew of plant matter eventually transforms to peat. In recent years, the peat-preserved bodies were disentombed, usually by an unsuspecting peat cutter harvesting the peat for fuel.

I read about others, most particularly Lindow Man, a 2000-year-old bog body that was discovered in 1984 near Wilmslow, Cheshire in a peat bog formed by the once much larger Black Lake. Scientific study determined that before the body was deposited in the ancient lake, the head was bashed, the neck garroted, and the throat slit. The findings were in keeping with a sort of ritualistic overkilling that archaeologists had seen elsewhere and that they surmised was undertaken as an offering to earn the favour of multiple gods. Though human sacrifice of the age typically involved individuals considered of lesser value, further study of Lindow Man suggested that he was highborn, perhaps even a druid who went willingly to his death. Radiocarbon dating placed the sacrifice firmly within the same half century as the Isle of Anglesey druid massacre and Boudicca’s rebellion. The timing led archaeologists to hypothesize that the high stakes of the period had provoked the Britons and their druid leaders to break with tradition and to offer the gods a man deemed of exceptional worth.

As I read, I wondered about a society so firm in its beliefs that humans were sacrificed, possibly with consent, to guarantee the next year’s crops or to ensure success on the battlefield. What would it be like to believe—beyond a shadow of a doubt—that the gods could be angered and then bribed to end the deluge of rain that would rot the wheat needed to survive? I pondered, too, the beauty and simplicity of a community that lived and breathed its daily and seasonal rituals, that was bound to the land in the most exceptional way. With the inferences about Lindow Man’s life and death as bedrock, I would write a story that explored living in the Iron Age—the close ties to the natural world, the pagan traditions and superstitions, the gods who dealt mercy or vengeance, the druid emissaries who interpreted divine will.

CATHY'S RESEARCH TRIP (click to enlarge)